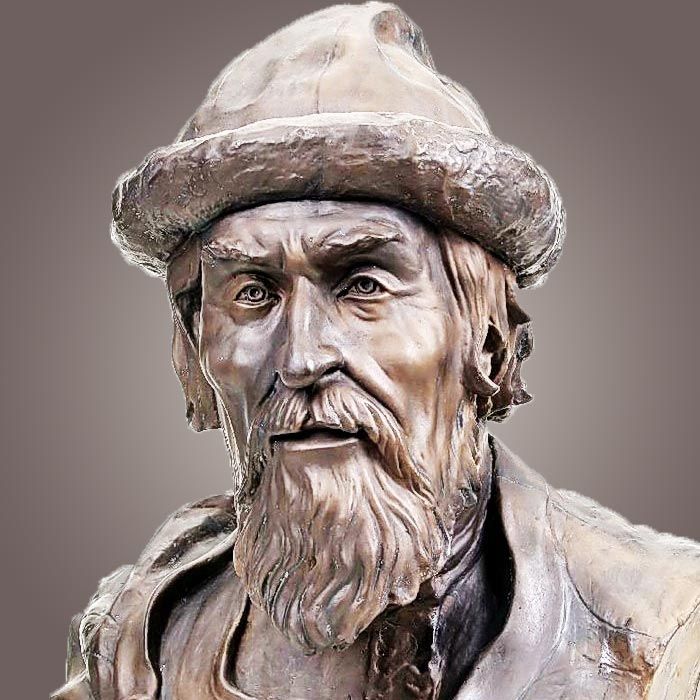

Yaroslav the Wise / Ярослав Мудрый

Last time, we saw that when Vladimir died, Svyatopolk was able to take power in Kiev and kill his brothers Boris, Gleb and Svyatoslav. At this point, Yaroslav moved south, fought him and drove Svyatopolk into exile. However, Svyatopolk returned with his father-in-law Boleslaw, King of Poland, who beat Yaroslav’s army in a surprise attack. Svyatopolk returned to Kiev to reign, but not rule: Boleslaw was in charge now. To remove the immediate obstacle to his rule, Svyatopolk betrayed his ally and father-in-law and sent out an order to kill the Polish garrisons in the cities of Russia. An almost defenceless Boleslaw took hostages and treasures from Kiev and returned to Poland, leaving Svyatopolk to face Yaroslav alone. Svyatopolk fled to the Pechenegs, came back with an army and faced Yaroslav at the spot where Boris had been killed. Yaroslav’s army won the day and Svyatopolk fled west once more, finally dying in the mountains between Poland and Bohemia. Yaroslav was now Grand Prince of Kiev and ruler of Russia.

The seniority of Vladimir’s sons is a complicated business, sources are unsure as to whether Yaroslav was born in 979 or 989 or sometime in between. The PVL states that Yaroslav was the son of Rogneda, although it is possible he was the son of another wife, possibly even of Anna, the sister of the Roman Emperors Basil and Constantine, if the later birth date is correct. Yaroslav’s remains were investigated in the 1930s and the estimated age at death was thought to suggest a later birth date and therefore a greater likelihood of him being the son of Anna or illegitimate. In his youth, he was sent to rule Rostov and the north east borderlands1, where, in 1010, he founded the city of Yaroslavl’.2

The Thaw, Yaroslavl, Aleksey Savrasov, 1874. The area by the church at the top of the river bank was the site of Yaroslav’s original fortress.

In the same year as Yaroslav laid the foundations for Yaroslavl’, Vladimir moved him to Novgorod to replace his older brother Vysheslav, who had died without issue. Within four years, Yaroslav had decided to refuse to pay tribute to Vladimir, one wonders if he saw the move to Novgorod as a demotion. Vladimir was given Novgorod by Svyatoslav because neither of his brothers wanted it and although it had been a good base for Oleg and, later, Vladimir to conquer the south, maybe it was seen as second best compared to the principalities closer to Kiev. In any case, within four years of the transfer, Yaroslav had stopped the payments to Kiev and precipitated the crisis that lead to years of war.

This period of Yaroslav’s life, as Prince of Novgorod, sees one of his most important achievements: the issuing of what has become known as the Most Ancient Justice / Древнейшая Правда or Yaroslav’s Justice / Правда Ярослава, in 1016 or 1017. The original text did not make it, but copies in Novgorod chronicles show a document with eighteen articles covering various aspects of justice. Yaroslav’s Justice allowed for murder and assault to be dealt with an act of revenge by the victim or close male relative – a brother, son or nephew. This was a very restricted list compared to many similar law codes; an obvious attempt to encourage a judicial approach, rather than blood-feud. If an willing avenger could not be found, a fine of forty grivnas (eight kilograms of silver) would be paid for murder or the loss of an arm. For an assault with fists, a blunt instrument, a (small) knife or the handle of a sword, the fine would be twelve grivnas (2400 grams of silver) as it was for damaging the moustache or beard – clearly these were signs of manhood and cutting them were considered serious attacks on a man’s dignity. Many other more minor offences were punished with a three grivna (600 gram) fine: riding or using a horse, using a weapon or wearing other people’s clothes without the owner’s permission, shoving another man (two witnesses were needed for this), damaging a man’s finger, late payment of a debt, hiding another man’s slave etc.

Yaroslav’s Justice also formalised procedural questions, setting out the levels of evidence (numbers of witnesses etc.) needed to prove various questions, and also stating the means by which decisions were to be made. For questions of theft, where, unlike assault, the act was done secretly, in the event that stolen goods were found in someone’s keeping, the two sides would meet before something like a jury of twelve people of good character, the defendant could bring witnesses to prove that he had acquired the stolen item from a third party in good faith, the third party would be brought and so on, until the person without a good excuse for having the stolen item was found and punished. This process would also help ensure that buying and selling was carried out in public markets in which the sellers would have paid a little tax to bring their wares for sale. A public purchase would help provide witnesses, while buying on the quiet, tax free, would not.

Yaroslav’s Justice bears many resemblances to other Germanic law codes: the same sort of choice between vengeance or fine, the treatment of intentional damage or violent crime and negligence as both being fixable through compensation, similar systems of proving a case can be found in early Anglo-Saxon law codes. Neither Biblical examples, nor Roman law seems to have had much of an influence at this point, possibly because of Novgorod’s role as a staging point and recruiting centre for new influxes of Viking warriors to join princes’ warbands. In any case, although this law code was initially only applicable to Novgorod, it was incorporated in later law codes covering the whole country and was taken as a contributory document in the publication of the Sudebnik, a general law code published in 1497.

Sitting on the throne in Kiev – nice.

In 1019, having driven Svyatopolk out of Russia into eternal exile, the PVL says Yaroslav sat in Kiev and he and his warband wiped off the sweat, having shown a victory and a great labour. Yaroslav’s first wife Anna had been taken to Poland, along with a possible son Ilya, with Boleslaw, never to return, and he married Ingigerda, the daughter of King Olaf of Sweden and Estrid, a princess from the Slavic tribes living along the Elbe. This marriage was blessed the next year: his eldest son we are sure existed, Vladimir, was born, but the year after that, 1021, trouble returned when his nephew Bryachislav, ruling in Polotsk, took advantage of his absence to raid Novgorod, returning with great wealth and prisoners. Unfortunately for Bryachislav, Yaroslav was very quick to respond and on the seventh day after leaving Kiev, he intercepted Bryachislav at the river Sudoma, beat his army, took back the treasure and freed all the prisoners. Bryachislav withdrew to Polotsk and the two men came to an agreement which settled the conflict.

Bryachislav runs away, Yaroslav rides home.

In 1022, Yaroslav went to besiege Berestye on the far western border with Poland while his brother Mstislav in distant Tmutarakan’ set out on campaign against the Kasogs. The Kasog Prince Rededya led his army out and when they met, Rededya suggested fighting man to man, rather than see the waste of life in a full scale battle. Mstislav agreed to the terms: the winner would take the loser’s wealth, wife, children and land. Mstislav suggested a wrestling match, rather than using weapons, to which Rededya agreed. The two men fought for a long time and it looked like Rededya was getting the upper hand, when Mstislav prayed to the Virgin Mary: “Oh most pure Mother of God, help me! If I overcome this man, I will raise up a church in your honour!” He was filled with strength and threw Rededya to the ground, picked up a knife and slit his throat. The Kasogs obviously didn’t consider the use of the knife to be cheating3, as they allowed Mstislav to take Rededya’s wife, children and wealth, to impose a tribute upon them and to enter Mstislav’s service as his vassals.

The struggle between Mstislav and Rededya, Nikolai Roerich, 1943.

The fight with Rededya was the prelude for Mstislav’s struggle with Yaroslav. Having acquired new Kasog, Yas and Khazar reinforcements for his army, Mstislav paused to build the church dedicated to the Virgin Mary, as promised, then in 1023, moved against Yaroslav, taking over the lands of the Severyane immediately to the east of Kiev. Although he attempted to take Kiev in 1024, the inhabitants resisted him and Mstislav withdrew to Chernigov and ruled the area to the east of the lower left bank of the Dnieper from there, and waited for Yaroslav to come.

Mstislav and his army.

Yaroslav was still in Novgorod at that time, but was unable to come south straight away because a rebellion had erupted near Suzdal. There had been a poor harvest in this region that year (unusual, as the soil around Suzdal is particularly fertile). Pagan priests who had lost their influence since the conversion to Christianity took advantage of the situation to provoke the hungry crowds to attack servants of the crown, claiming they were hiding all the food. Yaroslav went to Suzdal, executed the ringleaders and exiled the other pagan priests, while sending trading ships to the Volga Bulgars to buy food for the hungry population.

Having sorted out the rebellion to the east, Yaroslav returned to Novgorod and sent abroad for Viking warriors to join him. Their leader Hakon (known as Yakun the Blind / Якунъ сьлѣпъ in the PVL, but this could be a copying error for “the handsome” / сь лѣпъ – a blind man is unlikely to make a good warrior) had a most noticeable cloak, lavishly decorated with gold thread. With these Viking reinforcements, Yaroslav moved south to deal with Mstislav.

As night approached, the armies met at the river Listven, to the north of Chernigov. Yaroslav placed his Viking warriors in the centre of his line to punch a hole through Mstislav’s army, while Mstislav, taking an example from Hannibal at Cannae, put his recently recruited Severyane followers in the centre, while placing his seasoned warriors, both his warband from Tmutarakan’ and the Kasog and Yas fighters who joined him after Rededya’s defeat, on the wings. As darkness fell, a storm broke, and to the accompaniment of thunder, lightning and driving rain, Yakun’s men lead Yaroslav’s advance and cut into the Severyane force, pushing them back. Just when Yaroslav’s men thought the battle was won, Mstislav’s men drove into Yaroslav’s flanks; his army broke and ran. Yakun’s retreat was so urgent, that he left his golden cloak on the sodden field of battle, to the delight of Mstislav and his men. Looking upon the dead, he said “Who is not pleased by this? Here lays a Severyanin and here a Viking, but my warband is whole!” Yaroslav withdrew to Novgorod, Yakun sailed off home without his cloak, and Mstislav sent a message to Yaroslav proposing a deal: “You sit in Kiev – you are the older brother, and I shall have this side of the Dnieper.” Yaroslav remained very cautious, so he remained in Novgorod while his servants ran Kiev and Mstislav ruled the south east borderlands of Russia from Chernigov. While he was in Novgorod, Izyaslav, the son who would succeed him, was born.

Who is not pleased by this? By the way, take a message to my brother saying he can have Kiev as long as I get to keep Chernigov.

By 1026, Yaroslav had collected a force large enough to feel confident to move south and rule in Kiev again and the two brothers swore a peace on the basis of Mstislav’s suggestion. The peace proved permanent, the two brothers co-operating well with Mstislav in his geographical position and with obvious military talent serving as the first line of Russian defence against the Pecheneg threat to the south east. Over the next few years, things were relatively quiet: in 1027, the PVL reports that Svyatoslav, Yaroslav’s third son, was born, while the next year was notable for the appearance of a comet (a snake-like sign in the sky visible to the whole earth). In 1029 “it was peaceful”.

Finally, things liven up in 1030. Yaroslav becomes a father for the fourth time, calling his son Vsevolod. He also led a campaign on the western borders, taking the town of Belz from Poland and then moving north to tackle the Chud’ (ancestors of the Estonians in this case) and founded the town of Yuriev (named after St. George / Yuri, in whose honour he was baptised, now named Tartu). According to the PVL, “at that time” Boleslaw died and there were significant uprisings in Poland, but it seems that the chronicler might be mixing up his dates, Boleslaw was already five years in his grave and the rebellion came later. However, in 1031, Yaroslav and Mstislav joined forces to retake the rest of the Red Russian cities that Boleslaw had taken, founding a new town / fortress in the region, Jaroslaw, and capturing a large number of prisoners. The next year, Yaroslav founded a number of fortress along the river Ros’ to the south west of Kiev, settling his Polish prisoners there, including another town called Yuriev, now Belaya Tserkov’ (White Church).

The boys are back in town: Yaroslav and Mstislav take back the Red Russian cities.

Again, we have a few quiet years, until 1036, when Mstislav goes out hunting in poor weather, falls ill and dies. His son Yevstafiy had died in 1033, so rule over Chernigov returned to Yaroslav. Yaroslav went up to Novgorod, appointing a new bishop and placing his son Vladimir as Prince of the city. He also received a report that his remaining brother Sudislav, Prince of Pskov (just to the south of Novgorod) was acting against him, so arrested him and kept him imprisoned for the rest of Yaroslav’s life.

All change in Novgorod: Vladimir becomes Prince and Luka becomes Bishop.

However, now Mstislav was out of the way and with Yaroslav up in the north, the Pechenegs took advantage of the situation and attacked Kiev. Yaroslav collected an army of Vikings and northerners and returned to relieve Kiev. Before the city were Pechenegs “without number”, so he led his forces out to confront the beseigers at the future site of the Cathedral of St. Sophia. Vladimir had expanded and improved the defences of the walled area of Kiev. However, on the model below, the city at the time encompassed only the smaller area on the top left hand corner, surrounded on three sides by the wooded slopes. St Sophia’s Cathedral can be seen in the walled enclosure in the middle of the larger walled area on the top middle and right. This was open ground to the south of Vladimir’s city in 1036.

stvo99, CC BY-SA 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0, via Wikimedia Co

Yaroslav placed his Vikings in the centre, Kievans on the right and the northerners on the left hand side. If you are thinking “Isn’t that what he did when he lost the battle against Mstislav?” you’d be right. However, this time, the Pechenegs attacked. Things went well for Yaroslav and at the end of a long day’s fighting, the Pechenegs were defeated. The routed remnants of the Pecheneg force blundered about in the dark trying to escape through uneven, unfamiliar terrain; many stumbled into rivers and marshes and drowned. The Pechenegs were never again to seriously threaten Russia. It seems like, with Mstislav out of the way, they had bet everything on this assault on Kiev and having failed, with huge loss of life, scuttled off to find easier pickings on the borders of the Roman Empire. Just as the Pechenegs filled a vacuum left by the Khazars and Magyars, so this new vacuum would soon be filled, but for the rest of Yaroslav’s reign, the eastern borders were quiet.

The Pechenegs flee: don’t let the door hit you on the way out.

The next year, 1037, Yaroslav started work on that huge expansion of the walled city of Kiev seen in the photograph above (the city was eight times larger at the end of Yaroslav’s reign compared to the start). Aside from the Cathedral of St. Sophia (or more properly, of the Holy Wisdom – Sophia is a personification of the divine wisdom, not a human saint), Yaroslav founded a couple of monasteries, one named after St. George (like him) and the other after St. Irina (his wife was baptised Irina) and placed a church on the Golden Gates of the new part of the city. Here is a model of what Yaroslav’s St. Sophia looked like in Kiev’s National History Museum.

Качанов Сергій, CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wiki

And here is a reconstruction / renovation of the Golden Gates of Kiev with the Church of the Annunciation on top. On the photo of the model of the whole city, the Golden Gates are at the corner of the city at the very top right of the model.

Håkan Henriksson (Narking), CC BY 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Along with the new monasteries, Yaroslav collected scribes to copy and write books for the education of the newly Christianised elite. One of these literate churchmen was Ilarion, a monk who wrote one of the first literary (albeit with political / religious themes, not fiction) works to survive in Russian, who later became the first Russian Metropolitan of Kiev. Yaroslav’s money was not only spent in Kiev: he made sure to set up churches across the country with endowments to pay for priests to spread the word of Christ.

Yaroslav’s Scriptoria, copying out books as fast as we can.

After this burst of activity, the attention of the Grand Prince returned to the western border. In 1038, there was a campaign against the Yotvingians, in 1040, one against their neighbours to the north, the Lithuanians, and then in 1041, against the Masovians to the south. Around this time, Yaroslav arranged for the marriage of his sister Maria to Casimir I, the Duke of Poland, while his son Izyaslav married Casimir’s daughter Gertruda. The two rulers formed an alliance against the Masovians who had broken away from Poland and who were a source of instability for both neighbours. The alliance also confirmed Russian control over the towns of Red Russia. As part of the deal, in 1043 Casimir released the last of the prisoners held since Boleslaw’s retreat from Kiev in 1018; eight hundred men survived to make it home to Russia.

Yaroslav also married off his daughters to various royals, in 1038, Anastasia (possibly, the name is only recorded in a later Polish history) married the exiled Hungarian Prince Andras, who became King of Hungary in 1046. His daughter Elizaveta married Harald Hardrada, soon to be King of Norway in 1043, while his youngest daughter Anna married Henri I of France in 1051. There is a theory that Agatha, the wife of Edward the Exile (and therefore ancestor of the Plantagenet Kings of England), who had spent time in Yaroslav’s court after Canute took over Sweden, was another of Yaroslav’s daughters, click on the link to see more details about the arguments around who she really was.

Yaroslav’s son Vladimir was starting to get involved with the defence of the realm. In 1042, he leads a campaign against the Yam’ and wins. There is some debate as to where this took place, as some think it might be nearer Lake Ladoga. However, Yam’ was used to describe the southern Finnish area called Tavastia (Häme in Finnish). Whereever it was, Vladimir’s horses were affected by some kind of illness that loosened the skin, such that it was possible to pull off the hide of a still living horse.

In 1043, Vladimir is asked to lead an expedition against the Roman Empire, supposedly to take revenge for the murder of a notable Russian in Constantinople, but most probably in support of the rebellion of George Maniakes. Vladimir is given a fleet and makes it to the mouth of the Danube. However, as they approach Constantinople, disaster strikes and, according to the Russian sources, the fleet is damaged by a storm and is scattered. The Romans claimed their fleet and the application of Greek Fire may have had some role to play. Vladimir had to be rescued from his sinking ship by Ivan Tvorimirich, one of his commanders; six thousand warriors from the damaged ships made it to shore and another of Vladimir’s commanders, Vyshata, tried to lead them back to Russia on foot. The Roman Emperor Constantine IX sent a fleet to deal with the remains of the Russian forces. The PVL claims Vladimir smashed the Roman ships then sailed for home. However, the men on foot were captured near Odessos (Varna, not modern Odessa!), they and Vyshata were led back to Constantinople and many of them were blinded.

Vladimir is saved from the sinking ship.

1044 sees some unusual activity: Yaroslav digs up the bodies of his uncles Yaropolk and Oleg, has the bones baptised, then has them reburied in the Tithe Church alongside their brother Vladimir. As Olga and Vladimir had died Christians, and both Svyatopolk and Igor were killed and dismembered away from Kiev, Yaroslav managed to give all the pagan Grand Princes in easy reach a Christian burial. These are not the only princely burials: Bryachislav of Polotsk died, leaving the principality to his son Vseslav. Vseslav was said to have been conceived through wizardry and was “born in a shirt” (i.e. came out with part of the amniotic sac covering his head), which he kept with him all his life and which, according to the PVL, made him merciless when blood was being shed.

Yaropolk and Oleg are posthumously baptised and Vseslav becomes Prince of Polotsk.

I’ve been looking forward to 1045 because the PVL mentions it as the year St. Sophia Cathedral in Novgorod was started, by order of Vladimir and Bishop Luka. The roof has been rebuilt after a fire, but, unlike the churches mentioned in Kiev, this building has lasted to the present day, even some of the 11th century frescos have survived. The photo below shows its beauty from the outside:

User№101, CC BY-SA 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

but the fresco covered walls, closely packed pillars and relatively few windows gave the interior a unique atmosphere that isn’t really shown with a photograph taken on a well lit summer day: a feeling of mystery and of the Divine presence. I visited on a winter day without much bright sunshine, the photograph that most closely captures what I saw is here:

By https://wikimapia.org/user/799555, NiGhTDozoR: Egor Druzhinin

In 1046, Yaroslav and Constantine IX settle the last war ever between Russia and the Roman Empire. The settlement underlined the heights to which Yaroslav had raised the status of Russia. In 988, the Romans had been extremely reluctant to send a princess to marry the Grand Prince himself after Vladimir had captured Korsun’. Now Constantine IX sent his daughter Anastasia to marry, not Yaroslav, not Vladimir, but Vsevolod – Yaroslav’s fourth oldest surviving son. Constantine IX’s family name was Monomachos. This name passed down to Vsevolod and his most famous son, Vladimir Monomakh, who was born in 1053.

In 1047, Yaroslav and his brother-in-law Casimir joined forces once more to fight the Masovians, this time crushing them completely, killing their prince Mieclaw and re-incorporating the region into Poland. Apart from this, things remained quiet on the foreign policy front, although Yaroslav was not immune from tragedy: in 1049, his wife died and in 1052, Vladimir, clearly intended by Yaroslav as his heir, pre-deceased him, to be buried in his recently completed cathedral.

Yaroslav and Casimir sort out the Masovians.

The previous year, 1051, Yaroslav had reached what was probably the peak of his power and influence when he called a church council in Kiev and appointed Metropolitan Ilarion as head of the Russian church. In theory, the mother church in Constantinople would appoint the head of the Russian church, normally sending out a Greek speaking Roman citizen, but this time, Yaroslav’s prestige was great enough that he could set his own conditions and the Patriarch in Constantinople, and Emperor Constantine IX had to swallow their pride and accept Yaroslav’s choice.

Ilarion becomes Metropolitan Bishop of Kiev.

As his health declined, Yaroslav gathered his sons together to agree a secure and peaceful succession; no doubt the examples of the fratricidal conflicts that broke out after both Svyatoslav’s and Vladimir’s deaths were weighing heavily on the mind of a man who had five surviving sons. He exhorted them to live in love and peace with each other, for if they don’t, they will destroy the land of their fathers who had united it with such great trouble. He set his oldest surviving son Izyaslav, at that point ruling Novgorod and Turov, to rule after him in Kiev. Svyatoslav got Chernigov, the large principality covering much of the south east frontier all the way up to and including Murom, Vsevolod received a new principality at Pereyaslavl, to the east of Kiev as well as Rostov in the far north east. Igor was set to rule over Vladimir in Volhynia on the border with Poland, and Vyacheslav got Smolensk, in the centre of Russia with no external border. Polotsk remained with the descendants of Izyaslav Vladimirovich, at that time, Vseslav Bryachislavich.

Yaroslav passed away in February 1054, possibly on 20th February, and was buried in St Sophia’s Cathedral in Kiev.

Next time, we’ll learn all about Izyaslav – Find out in the next episode whether he managed to stick to his father’s advice about living in peace with his brothers.

RATINGS:

Length of Reign: Yaroslav was Grand Prince of Kiev for a most impressive thrity-five years. It is unclear as to when he was appointed as Prince of Rostov by Vladimir, many assume it was at birth, which they put as having been in 978. Other evidence suggests a later birth date and simultaneous appointment as Prince of Rostov in 987 or 988, which would mean he was Prince of Rostov and then Novgorod for at least thirty-one years prior to defeating Svyatopolk, giving him a grand total of 9 out of 10 points.

World Fame: At our cut-off point in November 2023, Yaroslav’s biography was on Wikipedia in fifty-seven languages, giving him 6 points out of 20.

Acheivements: Yaroslav was the first ruler of Russia to be described a Tsar (Tsezar’/Caesar), albeit only once, on a fresco in St. Sophia, Kiev; he was also the first to be generally known as the Grand Prince in his lifetime. His rule is widely recognised as the high point of early Russian history, his ability to come to a deal with his rivals and to deal with conflicts peacefully gave Russia a third of a century of stability without the fratricide and war under both Yaropolk and Svyatopolk.

Coming to power shortly after the country acquired literacy through Christianity allowed him to stand at the source of written legal tradition, having issued both a general law code, and the Church Statute of Prince Yaroslav (although it is believed that most of the existing text that is referred to under this name does not actually date from his reign, but are later additions). His expansion of Kiev, the foundations of cities at or near the borders of his realm as well as near the heartlands and his funding of monasteries and churches and schools, including a school for three hundred students in Novgorod, lead to an uplift in both the economic and cultural life of the country. Aside from his own legislative output and the work of the translators he funded, his reign saw the first works of original Old Russian literature – Metropolitan Ilarion’s Sermon on Law and Grace and his other works.

His diplomatic skills enabled him to marry his daughters off to three Kings, of Hungary, Norway and France, the surprising thing is that two of those men, Andrew I of Hungary and Harald Hardrada of Norway were exiles when the marriages were arranged. He also managed to get high status wives for his sons: Izyaslav married Gertrude, sister of Casimir I of Poland, Svyatoslav’s second wife was Oda, an Austrian noblewoman, a kinswoman of both Pope Leo IX and Emperor Henry III of Germany. Vsevolod’s bride was the daughter of the Roman Emperor Constantine IX. This demonstrates the prestige that the Russian dynasty and the country as a whole had achieved – the highest powers in Christendom did not feel ashamed to ally their families with the Rurikovichi of Russia.

Although it was ultimately unsuccessful in preventing conflict between his sons, his division of Russia upon his death shows a clear understanding of the importance of both Novgorod and Kiev to the Grand Prince. Both he and Vladimir had used Novgorod as a base to oppose and ultimately to defeat the Grand Prince of Kiev, so Yaroslav ensured that Izyaslav held both Kiev and Novgorod, the two primary centres of power and wealth. Svyatoslav got Chernigov and Tmutarakan’, like Mstislav, but with a section closest to Kiev removed to create the principality of Pereyaslavl’, which was given to Vsevolod, along with Rostov, which would leave Chernigov surrounded, while Vsevolod’s land would be vulnerable from both Kiev and Novgorod thereby creating a sort of Russian Mexican standoff. Peace lasted for ten years after his death, a lot longer than after Svyatoslav Igorevich’s death, let alone Vladimir’s, so that too testifies to Yaroslav’s wisdom.

Yaroslav has done more than enough to get a big score, his failing to maintain peace between his sons more than a decade after his death is more excusable than his father’s failure to keep his own sons’ loyalty during his own lifetime and it is basically his only weak point. His positive achievements, on the other hand are huge. I’m going to give him 28 points out of 30.

Defence of the Realm: Yaroslav deserves a high score for this criterion as well. He lost only two battles that we know about as Grand Prince, on the Listven against Mstislav and indirectly in Vladimir’s campaign against the Roman Empire. On the other hand, his reign saw a series of successful campaigns to deal with enemies on the western and northern borders of Russia and most importantly, he drove the Pechenegs away from Russia permanently, giving the southern and eastern borders an almost twenty year break from nomadic raiding before the Torki and then the Polovtsy took up the baton.

The diplomatic efforts mentioned above cemented peace with Poland, but also meant that his sons-in-law were sitting on the thrones of Hungary and Norway, while his brothers-in-law ruled Sweden, the source of Viking warriors for Yaroslav’s armies. By marrying his son Vsevolod to the daughter of the Roman Emperor, he cemented a peace that turned out to be permanent, although that was partially because within a few decades both sides became too weak to undertake a conflict across the Black Sea, even if they had wanted to.

In terms of a rating, Yaroslav deserves to be up there with Svyatoslav, as although he faced internal opposition and lost a battle against his rival, Yaroslav did actually beat the Pechenegs properly, avenging the death of his illustrious grandfather in a way Svyatoslav would have no doubt appreciated. So I’m going to give him 17 points out of 20.

Bonus Points: Yaroslav is going to be a high scorer here as well. Although both the towns he named in his Christian name George have both changed their names, he still has two towns named after his original name: Yaroslavl’ in Russia and Jaroslaw in Poland. I say “towns” – Yaroslavl’ is a city with a population of over half a million people, centre of Yaroslavskaya oblast’, important enough to be portrayed on the 1000 rouble note in Russia, along with a picture of the statue of Yaroslav himself in Bogoyavlenskaya square:

Maybe it’s a stretch, but another reminder of Yaroslav’s time in charge is on the 5 rouble note: the St. Sophia cathedral in Novgorod:

Yaroslav also appears on the 2 grivna note in the Ukraine:

Yaroslav has been commemorated on postage stamps, including this one from the Ukraine, which also features Metropolitan Ilarion on the right, with a plan of Yaroslav’s expansion of Kiev: note the Golden Gates at the top and St. Sophia’s below Ilarion’s book. Yaroslav’s book is his law code.

and one from Russia, with the facial features clearly following Gerasimov’s sculpture mentioned below.

Yaroslav is interesting because he is the first ruler of Russia of whom we have a really good idea of his appearance. Not only was there a portrait of the royal family painted on the wall of St. Sophia that lasted long enough for a copy of Yaroslav’s depiction to be made (the colour photo shows the four ladies to the left on what remains of the original, believed to be his daughters):

Авторство: Неизвестен. http://artclassic.edu.ru/catalog.asp?cat_ob_no=&ob_no=15169&rt=&print=1Uploaded to the English Wikipedia by User:Ghirlandajo, Общественное достояние, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1975957

but we also have a very well preserved royal seal with a portrait carved in his lifetime as well:

Авторство: Неизвестен. http://na-skryzhalyah.blogspot.com/2016/09/blog-post_25.html, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=116444151

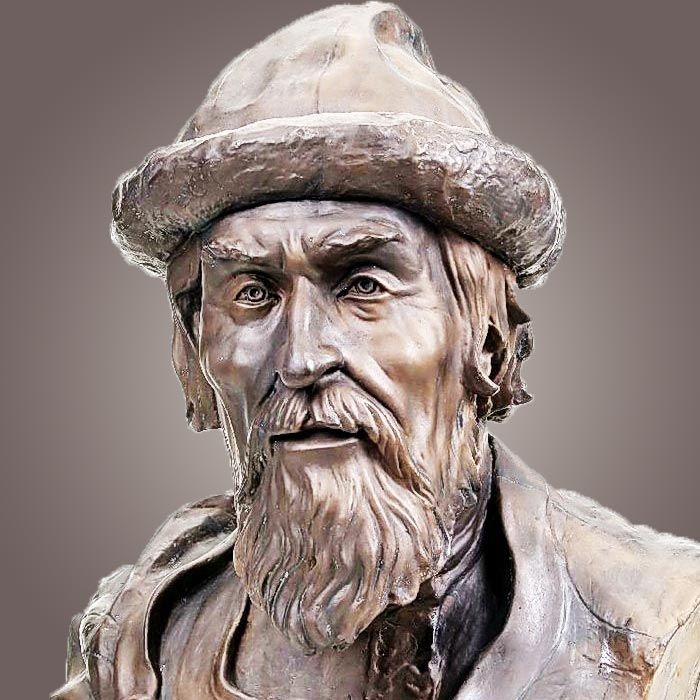

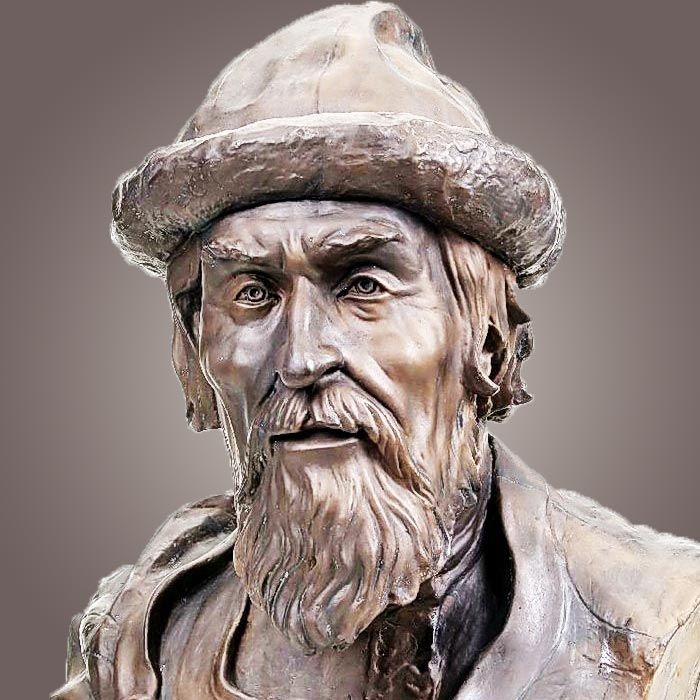

Finally, in the 1930’s, Yaroslav’s tomb was opened4, his skeleton removed, investigated and measured and these measurements used as the basis for a 1938 sculpture by Mikhail Gerasimov, the one at the top of this article, again here:

Although this must be the most lifelike statue, there are, of course, many others. As one of the greats, he features in the Alley of Russian Rulers in Moscow. There is a statue right next to his Golden Gate in Kiev, another one in the MAUP campus, one in Belaya Tserkov’, one in Kharkov, the one we’ve seen on the 1000 rouble note in Yaroslavl’, one in Novgorod outside the Technical school, and of course, on the Millennium of Russia monument, reading to Vladimir Monomakh:

Once upon a time…

Given his role in the development of learning and literacy and legislation in Russia it should be no surprise that universities carry his name: Novgorod University is named after him as is the National Law University in Kharkov. He has numerous streets named after him, two in Kiev, one in Melitopol’ (there was talk of returning the Soviet era name, that plan seems to have been dropped – it still seems to be named after Yaroslav), one in Kharkov, one in Sumy, while in Novgorod, the site of his residence is still known as Yaroslav’s Court, although the palace disappeared centuries ago.

Like all the greats, Yaroslav has a warship named after him, as well as an order of merit. Unlike most others, he was voted the greatest historical figure in 2008 in the Ukrainian TV show Velyki Ukraintsi / Great Ukrainians (Alexander Nevsky won the Russian version of the show). He’s had two films featuring him as the main character, one from 1981 named Yaroslav Mudriy (Yaroslav the Wise) and one from 2010 released as Iron Lord in English, but originally called Yaroslav – Tysyachu Let Nazad (Yaroslav – a thousand years ago) about Yaroslav’s rule in Rostov and the founding of Yaroslavl’, which had indeed happened a thousand years before the release of the film. Rurikovichi Part 2 covers Yaroslav’s rule of Novgorod, then Kiev from about 30 minutes to the end; he appears in Lestvitsa Vladimira Krasnoye Solnyshko, and in Yaroslavna – Koroleva Frantsii, a film about Anna’s rather dangerous journey across Europe to marry King Henri (she does make it, most of her bodyguards don’t) the film was based on a 1973 novel by Antonin Ladinsky “Anna Yaroslavna – Koroleva Frantsii”. He even appears in a couple of episodes in the second series of Vikings: Valhalla. Like his great-grandmother, Yaroslav has an opera in his honour by Yulii Meytus, first performed in 1973 called Yaroslav Mudriy, in turn based on a 1948 poem by Ivan Kocherga, but unlike Olga (as far as I am aware), Yaroslav also has a cantata written about him, first performed in Moscow in 2002.

There is one feature that I believe Yaroslav shares with only Ivan IV: a legendary secret library. Yaroslav’s is generally believed to be in or around St Sophia’s cathedral in Kiev, urban legends claim the library has even been uncovered during building work of such priority that it was decided to cover up the discovery and keep working, rather than pause to investigate. Some even claim Yaroslav’s library survived to become the basis of Ivan IV’s legendary collection. He also has a real library named after him in Yaroslavl’, the Yaroslav the Wise Central Children’s Library.

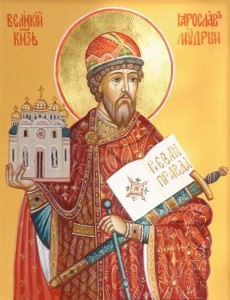

We started with Mammon, so shall finish with God: although Adam of Bremen mentioned Yaroslav as a saint back in the late 11th century, Yaroslav was only officially recognised as a saint by the canonical Orthodox Church in the Ukraine in 2004 and by the Church in Russia in 2005, his day of remembrance is 20th February, believed to be the anniversary of his death.

Saint Yaroslav the Wise, holding among other things, St Sophia’s Cathedral in Kiev and a copy of his law code.

With so many reminders of his rule, a major city and province bearing his name, a cantata and a legendary library, winning the Great Ukrainians competition and even getting a mention in President Putin’s 2024 interview with Tucker Carlson, I’m going to give Yaroslav the full 20 out of 20.

YAROSLAV’S RATING: 79 out of 100

Reflected Glory: One of the real strengths of Yaroslav was his ability to cut a deal with rivals, the most significant of whom was his brother Mstislav. According to the PVL, Mstislav seemed willing to be second best, provided his status was underlined with a principality greater than Tmutarakan’. His tactical genius was shown in the Battle on the Listven where he used Yaroslav’s strength, the army of Vikings, to his own advantage. His political savvy was shown by not trying to push for complete rule over Russia. Having been shown the door by the establishment in Kiev, Mstislav understood that it was better to serve in Heaven than rule in Hell. That the Pechenegs went all-in on an attack on Kiev as soon as Mstislav was dead is evidence of the role he played in defending the country, unnoticed by the chroniclers in Kiev. That the Pechenegs were unable to overcome the Russian army, and were so weakened that they went away and basically never came back would also suggest that Mstislav may have spent the previous ten years battering them.

Vladimir, Yaroslav’s son and presumably his preferred heir was another shining star, leading Novgorod from the age of fourteen until his death in 1052. He worked hand in hand with Bishop Luka, to entrench the cultural development of the city and to build St Sophia’s cathedral. He organised the building of a stone wall around the city to replace the earthen banks and wooden fortifications. He led a campaign to the north and was given command of the ultimately unsuccessful raid on Constantinople in 1043. Vladimir died a couple of weeks after the cathedral was completed and was buried there soon after. He was canonised in the 15th century with his day of remembrance on 4th October.

Bishop Luka Zhidyata of Novgorod was himself an impressive figure; he had been appointed Bishop of Novgorod in 1034 and was the first Russian to be so honoured – previous Bishops had mostly been Greeks from the Roman Empire. Although none of his translations are known to have survived, he was a notable translator of Greek language works into Russian. His work “Sermon to the brothers” may have been the first original spiritual work to have been written in Russian. He opposed the appointment of Ilarion as Metropolitan of Kiev, as he felt this should be the prerogative of the Patriarch in Constantinople. Unfortunately, having made that stand, a servant of his denounced him to Kiev for some crime, he was arrested and held for three years until it turned out that the accusation was malicious. The servant was mutilated in punishment and Luka was released. Sadly, he never made it back to Novgorod, dying on the journey to his diocese. Like his prince, Luka too has been recognised as a saint.

Finally a word about Metropolitan Ilarion. As mentioned, he was the first Russian to lead the Church in Russia. Orthodox Bishops must also be monks (although parish priests may and generally do marry), Ilarion was a Hieromonach, both a monk and a priest, serving at Berestovo, a princely compound near Kiev. Seeking quiet to pray, he would walk to the bare hill to the south of Kiev and dug himself a little pit for shelter from the wind and to keep him away from prying eyes. Later, a monk from Mount Athos, Anthony, dug himself another pit nearby and the area became the centre of the Pecherskaya Lavra Monastery in Kiev, the caves in question being extensions of these original pits. But Ilarion is famous for more than digging holes: he was the author of a number of works, the most notable of which is the Sermon on Law and Grace. His style was considered worthy of emulation by his successors and being in charge of the church at a time Yaroslav was funding learning meant that his example stands at the fount of a long tradition of spiritual writing in the Russian language.

If you find yourself in a hole, keep digging and establish a monastery listed on the UNESCO World Heritage site.

- Rostov is a town on the shore of Lake Nero, it is believed to have been a centre of the Finnic Meryan people, or rather the earlier site called Sarskoye Gorodishche was. This older settlement, a little way up the Sara river from the lake, had been a Meryan town since the 6th century. From 800 AD, it became a centre of trading, linked, by the river Kotorosl’, to the Volga trade route between Scandinavia and the Abbasid Caliphate. Rurik chose Rostov as the site for one of his centres of administration, after which nearby Sarskoye Gorodishche slowly declined.

The artist Nikolai Roerich was involved in the excavation of Sarskoye Gorodishche, the finds inspired him to create the painting above: They Build the City, 1902.

↩︎ - Yaroslavl’ is located at the point where the Kotorosl’ river joins the Volga, the confluence is at the end of a low lying spit of land overlooked by a hill on the high right bank of the Volga. According to local legend, the area was inhabited by a ferocious bear, believed to be divine, to which the locals sacrificed. Yaroslav headed a mission to convert the locals to Christianity, and to prove the strength of the Christian God, he fought the bear, killing it with an axe, and founded a town on the hill overlooking the spit. The coat of arms of the city shows the bear and the axe in honour of Yaroslav’s feat:

The top of the hill overlooking the spit currently houses the Dormition Cathedral, a replacement for the previous cathedral, destroyed in 1937.

A few miles up the Kotorosl’, near the village of Timeryovo, archaeologists discovered another Viking trading post which has revealed the largest hoard of Arab silver coins in Northern Europe. The latest coin found at that site was minted no later than 1057, so it looks like, as in the case of Rostov and Sarskoye Gorodishche, the foundation of Yaroslavl’ caused the trading activity to move to the more accessible site on the Volga, once the security of the new town was assured. Despite the wealth stored there, Timeryovo seems not to have had any walls or defensive structures. Its position up a smaller river, some distance from the Volga seems to have kept it safe enough for its inhabitants. ↩︎ - This is a little like the story of the Night of the Long Knives from British legend. In that story, the Britons make a peace deal with the invading English and cement it at a feast. To avoid trouble, all the guests had to give up their swords upon entry. During the course of the evening the guests got drunker, rash words were spoken and a fight broke out. Unfortunately, the Britons had forgotten that the English carried long knives (seaxes), which were not considered swords, so when the fight broke out, the English settled it with their knives, which they had not given up at the start of the feast. In this case, the Britons did consider the use of the knives cheating, but were in a weak position to complain about it, being dead. ↩︎

- The tomb has been opened since and Yaroslav’s remains were missing. It is suspected that they may have been stolen during the war by the Nazis, or nationalist Nazi collaborators and taken to the USA. A wonder-working icon that went missing under similar circumstances was recently found in a Ukrainian church in New York. ↩︎

Leave a comment