Svyatoslav / Святослав

After Igor’s death at the hands of the furious Drevlyane, his widow Olga takes over government. She teaches the Drevlyane and anyone else paying attention never to try anything like that again with a long series of acts of revenge. Once the Drevlyane were crushed, Olga travelled around Russia, setting up a formal system of tax payments to replace the in-person collection of tribute, which had led to Igor’s demise. Olga travelled to Constantinople to maintain the trading relationship, but also to convert to Christianity. Upon her return to Russia, she sent a message to Otto the Great, King of Germany, to send missionaries, but also handed power over to Svyatoslav, who wanted to remain pagan. He gave the missionaries a very poor welcome.

It is not clear exactly when the hand-over of power between Olga and Svyatoslav occured. The Povest’ Vremennykh Let (PVL) has several years of nothing happening between Olga’s trip to Constantinople in 957 AD (955 according to the PVL) and Svyatoslav’s first campaign in 964. Adalbert’s missionary activity was prompted by an invitation received by King Otto in 959 and ended by Svyatoslav’s lack of interest and hospitality in 961, suggesting Olga was still at least partially involved in international relations in 959, but was unable to prevent Svyatoslav from sending her guests packing two years later. For a discussion of the questions around Svyatoslav’s age, please see the footnote: 1 (Svyatoslav’s age)

Svyatoslav and his advisers, and him asking the Vyatichi to whom they paid tribute.

The first thing the PVL tells us about Svyatoslav in 964, after the few years of silence during the power transfer, is that he was very keen on fighting. He attracted a large number of warriors and went out on campaign “like a leopard” and conquered widely. Interestingly, the PVL even discusses his strategy – he goes out without a baggage train or cauldrons to boil meat, instead he would roast it over an open fire and eat it (this is quite unusual for mediaeval Europe, they would generally boil their meat for a long time to make sure any bugs were killed and to add flavour to the pottage). He and his men would not take tents with them, but use their saddle as a pillow and the blanket under it as bedding. Essentially, they were taking on the style of fighting of their closest neighbours on the steppes: the Pechenegs and Khazars – that of highly mobile cavalry forces. However, Svyatoslav was a more civilised and gentlemanly chap than those nomads. Before going on campaign, the PVL says he would send a message to his future hosts: “Хочю на вы ити” in the old Russian, or in modern terms – “I’m coming to get you.” His martial nature has defined his reputation: he is known as Svyatoslav the Brave.

The first people noted as offering Svyatoslav their involuntary hospitality are the Vyatichi, the Slavic tribe living some way to the north east of Kiev, along the valleys of the Oka and upper reaches of the Don. In 964, Svyatoslav went along the Oka, reaching the Volga (according to Arab sources, defeating the Volga Bulgars) and asked the Vyatichi to whom they paid tribute. They replied that they paid the Khazars one shchelyag (A shilling – in this case probably an Arab dirham, 3.9g of silver) from every household.

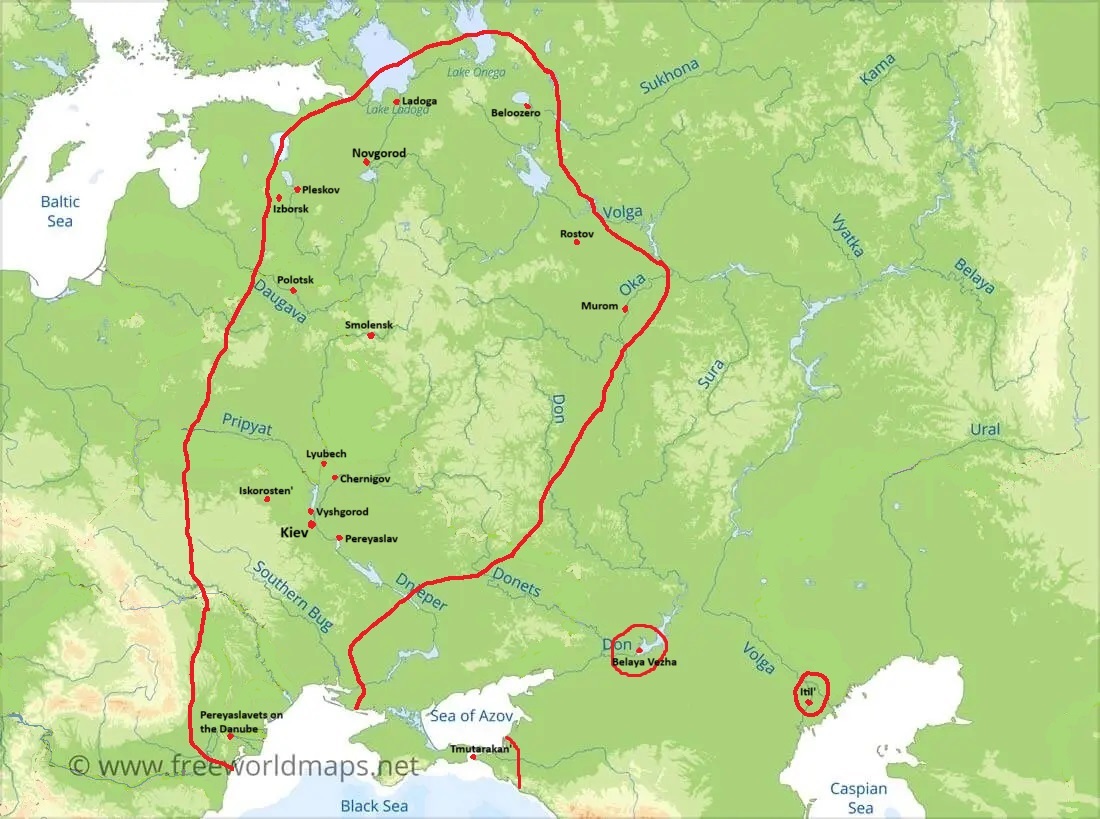

Next year, Svyatoslav goes against the Khazars. Please bear in mind that the Khazars had been the dominating power over the North Caucasus for centuries with their control stretching up the Don, the Volga, east to the Aral Sea and south beyond the Caucasus mountains. The PVL keeps it laconic: “Svyatoslav advanced on the Khazars. Having heard that, they went out to stop him, lead by their prince, the Khagan and they came together to fight and Svyatoslav beat the Khazars and took their capital and Belaya Vezha. He also beat the Yas and Kasogs.” And so the curtain pretty much falls on the Khazar empire. Their vassals stop paying tribute and Svyatoslav’s son Vladimir finally forces the remains to accept tributary status after 985 and their empire falls apart.2 Khazars

The map shows Khazar expansion up to 850AD, i.e. just before the Russian state begins to chip away at their westernmost vassals.

Svyatoslav’s campaign seems to have been rather more comprehensive than the PVL suggests. A contemporary account by Ibn Hawqal gives a slightly later date for the campaign – 968/969 AD – but says that Svyatoslav took not only the current Khazar capital Itil, but also Samandar, a previous capital on the coast of the Caspian sea. A Russian garrison was maintained in Itil until at least the 980s. Ibn Hawqal also states that Svyatoslav had reached the territory of the Volga Bulgars. In addition, the city Tmutarakan’ on the Taman’ peninsula also seems to have fallen into Svyatoslav’s hands, remaining a Russian principality for over a century.

Svyatoslav fights the Khazars.

It’s not clear from the PVL whether the Yas and Kasogs whom Svyatoslav beat were vassals who sent warriors to help the Khagan in battle, or as their homelands (Alania and Circassia) lay between Samandar and Tmutarakan, whether Svyatoslav bent them to his will on his way back home. Belaya Vezha (White Tower) was the new Russian name for the fortress and city on the Don previously known as Sarkel (White House in Khazar), which also remained in Russian hands until the 12th century. In 966, having removed the Khazar competition and the immediate threat to them from Sarkel, Svyatoslav re-visits the Vyatichi, imposing tribute on them and incorporating them into the Russian state.

Is that all the money you collected to give to the Khazars? Don’t worry, I’ll look after that now.

Very impressive, you are do doubt thinking. Svyatoslav crushes the empire which had been exploiting the Eastern Slavs for generations and sets up garrisons to maintain Russian control over strategic points on the Baltic – Caspian trade routes. At this point, he takes a rest… oh no he doesn’t, he almost immediately sets out to crush the Balkan Bulgars.

The Novgorod Chronicle had suggested that the Ulichi, living to the south of Kiev, had been subjected to tribute by Sveneld, under Igor’s rule, but they and the Tivertsy, who lived further to the west, seem to have been at least partially independent of Kiev at this point. The Pechenegs were both a threat to those tribes (eventually forcing them to move north-west) and a factor making it difficult for the Grand Prince in Kiev to exercise direct control over them. At least until Svyatoslav arrives.

In 967, the Roman Emperor Nicephorus Phocas, the White Death of the Saracens, asked Tsar Peter I of Bulgaria to help prevent Hungarian attacks on Roman lands in the Balkans. Peter refused, so Nicephoras sent an embassy to Kiev with over 450 kg of gold to persuade Svyatoslav to attack Bulgaria from the north. Svyatoslav proved amenable to persuasion and so he set out with an army in the tens of thousands (estimates range from 22,000 to 60,000). He moved through the territory of the Ulichi and Tivertsy and crossed the Danube into Bulgaria. The PVL gives the date of Svyatoslav’s overwhelming victory over the Bulgars as 967, having captured eighty towns from them and him taking up residence in Pereyaslavets on the Danube. A Roman historian Ioannes Scylitzes gave the date as 968.

However, in 968, Svyatoslav was forced to return to Kiev. This retreat was not caused by Bulgarian resistance, but by an attack by the Pechenegs. As we saw when discussing Olga’s later life, the Pechenegs had surrounded Kiev, cutting the city off from the river. She was in charge of the city and looking after Svyatoslav’s three sons: Yaropolk, Oleg and Vladimir. Using the courage and wits of a local lad who could speak Pecheneg, they let him out of the city with a bridle. He walked through the besiegers asking if anyone had seen his horse until he got to the river. He was clearly a fast swimmer as well as a linguist, as by the time anyone noticed him, he was beyond arrow range and was able to get away.

Why is that lad who was looking for his horse now going for a swim?

He found a Russian garrison who came and, with the help of noise raised by the inhabitants of Kiev and their own trumpets, the local commander Pretich was able to bluff the Pechenegs into withdrawing for a while. Olga managed to get her grandsons evacuated to the other side of the Dnieper while Pretich exchanged gifts with the Pecheneg Prince. In the meantime, messengers had been sent to Svyatoslav, who returned with the bulk of his army. He chased the Pechenegs away after which the two sides made peace, allowing Svyatoslav to think of returning to his Balkan campaign.

Svyatoslav returns to Kiev with his army.

Svyatoslav, for his part, clearly liked his new territories. When criticised by Olga for leaving Kiev undefended, the PVL quotes him as saying “I don’t like sitting in Kiev. I want to live in Pereyaslavets on the Danube. There is the centre of my land (clearly untrue, unless he meant the land he had only recently conquered), all the good things flow there: from the Greek lands – gold, silk, wine and various fruits; from Czechia and Hungary – silver and horses; from Russia – furs and wax, honey and slaves.” Svyatoslav promised to remain in Kiev while Olga still lived, but she died soon after (three days after the promise according to the PVL). Svyatoslav set his eldest son Yaropolk in charge of Kiev, Oleg in charge of the Drevlyane and Vladimir was sent up north with his uncle Dobrynya to look after Novgorod while Svyatoslav returned to take care of the Balkans.

Vladimir Svyatoslavovich goes to Novgorod. I wonder if we’ll ever hear from him again?

In 971 (according to the PVL; the Roman sources date the beginning of the second campaign to 969), Svyatoslav arrives at Pereyaslavets, only to find that the Bulgars were defending it. The two sides met in battle and, to start with, things went better for the Bulgars. Svyatoslav encouraged his men to remain courageous with the words “It looks like we may die here. Let us stand bravely, my brothers and fellow warriors,” and his exhortation seems to have done the trick. The Russians beat the Bulgars and Svyatoslav took Pereyaslavets back.

Svyatoslav takes Pereyaslavets.

By this time, the political situation in the Balkans was changing. Nicephoras Phocas had been surprised by the level of the defeat Svyatoslav had dished out to the Bulgars and was starting to worry that he was replacing the devil he knew with a rather more powerful and successful devil he didn’t. He made peace with Tsar Peter I and agreed to marry the junior Emperors Basil II (the Bulgar-slayer) and Constantine VIII to Bulgarian princesses. As you can guess from Basil’s future nickname, the marriages never took place. After the second defeat at the hands of Svyatoslav, Peter I abdicated, became a monk and died soon after, eventually being named a saint. Nicephoras Phocas partially followed Peter’s example, dying soon and becoming a saint, but rather than dying of grief, he died a horrific death at the hands of conspirators led by a general, soon to be Emperor John Tzimiskes.

John initially sought peace with Svyatoslav, offering him the final payment agreed with Nicephoras Phocas for the defeat of the Bulgars. Svyatoslav demanded additional payment to leave the conquered cities and for handing back the men taken prisoner. He also threatened that if John did not agree, he and his new allies would take all the Roman territories in Europe. His new allies being the new Bulgarian Tsar Boris II, Pechenegs as well as the Hungarians.

Nicephoras had already boosted the defence of the Roman lands in the Balkans in response to Svyatoslav’s successes, and John was further aided by the fact that a war in the east had ended with success for the Romans so reinforcements from that front were available. John had also sent spies into Bulgaria who could speak both Slavic and Greek to keep an eye on the Russian army. Svyatoslav and his allies crossed the mountains and moved towards Arcadiopolis, only 100 miles from Constantinople. According to Leo the Deacon, Svyatoslav had a low opinion of the Roman forces opposing them, thinking them to be conscripted craftsmen, not professional warriors. He led a joint force of Russians and Bulgars, while the Hungarians and Pechenegs were acting more or less independently. According to Ioannes Scylitzes, the Pechenegs fell into a trap and were almost completely wiped out. The same day, the Russians met another Roman force and after the death of a chieftain of huge size, sliced in two by the Roman commander Bardas Sclerus, the morale of the Russian army collapsed and they fled, having killed no more than fifty-five Romans. The Romans claimed to have killed 25,000 “Scythians“, while the PVL says Svyatoslav only had 10,000 to start with.

Svyatoslav fights the Romans and chases them from the field of battle.

Here is the Roman view of how things went – this time the Romans are chasing Svyatoslav’s men from the field of battle.

The PVL skates over this unfortunate series of events, preferring to concentrate on the peace negotiations and Svyatoslav’s hard bargaining to get a decent tribute out of the Romans despite this little upset. However, it does say that Svyatoslav was in a position to demand tribute because he had WON the battle with the Romans, which does not tie up with what the Romans were saying. Some historians have suggested that as the Romans admit the allied forces had split up, maybe the army that took a thrashing at Arcadiopolis wasn’t actually Svyatoslav’s main force, but rather his vassals and allies. Although the Romans had done well to destroy one of Svyatoslav’s armies, he may well have still been in the field with a dangerous force that would need dealing with, or paying off. It is possible that Svyatoslav might have run up against another Roman force that came off second best and this victory is what is referred to in the PVL. In those circumstances, both sides could (and clearly did) claim victory.

In any case, the PVL tells the story like this: the Romans purported not to have the strength to oppose Svyatoslav and asked him how many men he had, so they could pay them all a reasonable tribute. Svyatoslav had ten thousand men, but suspected a ruse, and told the Romans he had twenty thousand to try and scare them off. However, it didn’t work and the Romans sent out an army of one hundred thousand men to fight Svyatoslav. When his men saw the size of the force ranged against them they started to lose their courage. Svyatoslav told them “It’s too late to get out of this. Whether we want to or not, we’ll have to fight them. Rather than shame the Russian land, we’ll have to die here – dead men can’t be shamed. If we run, we’ll be disgraced, so let’s stand firm. I’ll go in front of you. If my head falls, then you can worry about yours.” His men replied “Where your head falls, ours will too.” The Russians fought wildly and there was a terrible slaughter – Svyatoslav overcame the enemy and the Romans fled.

The Roman Emperor consulted his advisors, asking “What do we do now?” They suggested sending Svyatoslav gifts and seeing his reaction to judge how best to pay him off. The envoys set off to Svyatoslav’s camp with gold and silks. They were led into his presence, bowed before him and presented the gifts. Svyatoslav didn’t even look at the gifts, he just told one of his pages to take them away. The Romans returned to the Emperor and told him what happened. One advisor said “Let’s try again. This time send him some weapons and see how he reacts.” So they sent him a sword and some other weapons and this time he took the gifts and praised the Emperor. When the advisors heard that, they said “This man will be ferocious – he ignores wealth but takes the weapons.” They agreed to pay him tribute, both for the living and the dead and he took the gifts and money and returned to Pereyaslavets.

Hmm. Nice sword. I think I’ll keep it.

However, seeing how few men he had left after all the fighting, he realised there was a fair chance someone might attack him and take all the wealth he had gathered. To protect his back, he travelled to the Emperor, who was at Dorostol, asking for a long lasting peace and friendship between them. He explained this to his men, saying that if the Romans realise how few of them there were, they might come and besiege them. They were too far from Russia for help to come in time, so instead, they should make peace with the Romans and take tribute from them. If the Romans stopped paying tribute in future, they would have the chance to get reinforcements from Russia.

John meets Svyatoslav at Dorostol.

Sveneld was left in Dorostol as an envoy and met John Tzimiskes and Bishop Theophilus. Sveneld recounted that Svyatoslav swore by Perun and Veles that he would be a friend to the Roman Emperors and Empire, that in future he would attack neither the Empire nor Bulgaria and nor would he encourage any other nation to attack them. He also promised to protect the Roman territories and cities on the Crimea. This was written down and the representatives of the two sides signed and sealed the charter and separated in friendship.

Sveneld and John Tzimiskes agree a treaty of friendship.

Finally, Svyatoslav decides to head off home to Kiev. His warband sailed up the Dnieper in boats until they reached the rapids. Sveneld warned Svyatoslav to ride past the rapids on horseback, because the Pechenegs would be waiting. Svyatoslav ignored the advice and indeed, the Bulgars of Pereyaslavets had sent a message to the Pechenegs to let them know Svyatoslav was on his way. Svyatoslav got to the rapids and found he couldn’t pass. He and his men were forced to spend the winter in the steppes with extremely limited food supplies.

When the spring of 972 came, Svyatoslav tried again to break through, but ran into the Pecheneg Khan Kurya who killed him, took his head and had it made into a wine cup (this is actually a sign of great respect among the Pechenegs – Kurya would have believed that some of Svyatoslav’s courage and expertise would flow to him as he drank wine from the cup). Sveneld escaped and made it back to Kiev to inform Yaropolk he was now the Grand Prince.

A Roman chronicle shows the Pechenegs killing Svyatoslav (the last word at the top right is Svyatoslav’s name in Greek).

RATINGS

Length of Reign: Svyatoslav was the Grand Prince of Kiev from 945 to 972, a total of 27 years. He might have been around for a bit longer if he had listened to Sveneld, but as it is, he gets 5 out of 10.

World Fame: As of November 2023, Svyatoslav’s entry on Wikipedia had been translated into 56 languages, giving him 6 points out of 20.

Achievements: Most of Svyatoslav’s achievements can be looked at under Defence of the Realm. As he was a particularly warlike Grand Prince, those elements of his rule we could discuss separately from that are few and far between. Although it was described as part of a campaign to the north east, it isn’t entirely clear if Svyatoslav’s 964 visit to the Vyatichi was peaceful or not. That the PVL does not record the Vyatichi paying tribute to Kiev until after the collapse of the Khazars may suggest that they simply let Svyatoslav pass in 964 as he went to knock out the Khazar’s northern vassals along the Volga. In which case, the incorporation of the rather large territory of the Vyatichi into Russia may well have been peaceful, although in the context of a war against the Khazars.

Under Svyatoslav, we also see final proof that the Ulichi and Tivertsy are now subject to Kiev, leaving only the Volynyane and White Croats to be incorporated under Vladimir, so he almost completed the work of unifying all East Slavic peoples under one state. By taking on the Khazars and occupying a number of their strategically placed cities – on the Don, on the Volga and on the exit to the Sea of Azov, Svyatoslav moved to expand Russian control over even more of the eastern trade routes, while transferring his base to Pereyaslavets meant he covered part of the Danube trade route into Central Europe as well.

On an administrative front, maybe because it is the first time a Grand Prince has left multiple living heirs, we see Svyatoslav’s sons given rule over various cities. As Svyatoslav had decamped to Pereyaslavets, he placed Yaropolk in Kiev, Oleg over the Drevlyane (in their new administrative centre Vruchy) and Vladimir in Novgorod, Rurik’s original capital. On one level, this is a sensible way of both ensuring power over strategic points remains in the family, while giving your heirs the opportunity to get used to political life and to acquire the skills needed to rule. On the other hand, it can be a recipe for disaster when the old Grand Prince dies and the sons all have independent power bases from which to compete for ultimate power.

This process generally leads to the weakening and break up of large states into smaller ones, but the idea of dividing an inheritance between sons was a strong cultural expectation, especially in the Germanic world the Rurikovichi came from, so it is not surprising they should follow the accepted customs in this regard. It may have helped maintain peace during Svyatoslav’s long absences, but it didn’t take long for the brothers to fall out once Svyatoslav had taken up his new career as a somewhat macabre goblet.

Finally, his policy of religious tolerance, despite the increasing influence of Christianity is, if not a positive strength, then at least an avoidance of internal conflict and external trouble. The Khazars, for example, asked for help from Khorezm (the recruiting ground for their Royal Guard) upon Svyatoslav’s invasion, but that kingdom refused to help unless the Khazars converted from Judaism to Islam. By letting people do their own thing, Svyatoslav at least didn’t make an enemy of any religion.

It’s a mixed bag, but generally a bit more positive than negative, so I’m going to give him 18 out of 30.

Defence of the Realm: Not since Oleg have we seen such a successful military leader in charge of Russia. Although the Khazars might have been weakening, taking down the power which had not so long ago demanded tribute from much of the south and west of what had become Russia was still a major achievement. Taking out a nomadic power is always dangerous, as it opens the door for a more ruthless successor to swarm in and cause trouble, but in this case, the Pechenegs had already arrived in the steppes north of the Black Sea, so there was no immediate danger. By taking control of their major cities and possibly defeating the Volga Bulgars, Svyatoslav stamped Russian authority over the key points of the Volga – Caspian – Caliphate trade route. By dealing with the Alans and Circassians in the north Caucasus, he also neutralised the possibility of them threatening his new territories.

Occupying Itil, Belaya Vezha and Tmutarakan was ambitious, although Itil was abandoned fairly soon after, the other two remained under Russian control for over a century, showing Svyatoslav was able to make lasting gains in difficult-to-control territory (both cities were beyond the Pecheneg steppes, so not necessarily easy to supply or defend from Kiev).

The move into the Balkans was even more ambitious, especially as Svyatoslav at first seemed convinced of the wisdom of moving the his capital to Pereyaslavets on the Danube. After defeating the Volga Bulgars, the Khazars, their vassals the Alans and Circassians, accepting the tribute of the Vyatichi as well as chasing off the Pechenegs, Svyatoslav might have thought no-one could stand in his way. The collapse of Bulgar resistance must have confirmed that, so when the Romans started to act against him, the temptation to try and knock out the premier power in the eastern Mediterranean was clearly too much to resist. The PVL gives indirect evidence of at the very least, a high casualty rate for Svyatoslav’s army in his fight with the Romans, even if Leo the Deacon’s account seems exaggerated.

Although holding on to Pereyaslavets would have given the Russian state an even greater hold on the Black Sea / Caspian trade routes, it seems like this campaign was a step too far. Although Svyatoslav was able to withdraw from the Balkans with wealth and honour, the losses the Romans had inflicted were clearly the reason his warband was unable to force their way through to Kiev in 791 and why, weakened by hunger and cold, they fell victim to the Pechenegs in the spring of 792. Although the other conquests remained under the rule of his successors, the far south-western territories were relinquished soon after Svyatoslav’s death. I suppose there are two lessons to be learned here: after hubris comes nemesis and never trust a Pecheneg.

Losing so many men to the Romans that you end up as the Pecheneg Khan’s cup is a sad end to an impressive military career, but if he had listened to his mother and become a Christian, he would have known that those who live by the sword die by the sword. In any case, he can’t get full marks here, but for a remarkable life that undoubtedly put Russia’s security on a far firmer footing for his sons to enjoy, I’ll give Svyatoslav 17 marks out of 20.

Bonus marks: Svyatoslav is the first ruler of Russia for whom we have a written description, although many think Leo the Deacon’s pen portrait is a little too like Priscus’s description of Atilla the Hun to discount the possibility of a little plagiarism. In any case, the picture by Fyodor Solntsev at the top of this post is based on the description. So now you know what Atilla the Hun looked like too.

Svyatoslav has been the hero of a number of literary works, starting with Yakov Khyazhnin’s 1772 play “Ol’ga” and Nikolay Nikolev’s 1805 tragedy “Svyatoslav”. Kondraty Ryleev wrote one of his “Dumy” about Svyatoslav and Velimir Khlebnikov wrote “Napisannoye do Voyny” (Written before the War) about Svyatoslav’s death. He remains a figure of interest up to today, with, for example, the historian Vadim Kargalov writing a historical novel about him in 1989 and the pagan author Lev Prosorov releasing “Svyatoslav – Rod i Rodina” (Svyatoslav – Clan and Motherland) in 2006. Svyatoslav has made it into English language literature as the villain in Samuel Gordon’s 1926 novel “The Lost Kingdom”. While it’s not exactly a literary work, Dinamo Kiev’s fanzine is named after Svyatoslav (he is also the symbol of the Dinamo Ultras).

For obvious reasons, not least that he only outlived Olga by three years, Svyatoslav features in many of the same films and TV programmes as his mother Rurikovichi – episode two this time!, Kreshchenie Rusi, Legenda o Knyagine Ol’ge for example. Svyatoslav also appears in the second of a series of cartoons about the history of Russia and the Volga Bulgars, Saga Drevnykh Bulgar: Lestvitsa Vladimira – Krasnoye Sol’nyshko.

Svyatoslav has inspired the construction of a number of monuments, the first seems to be a tablet set up in 1910 at one presumed site of his death in the Dnieper rapids. Another plaque was set up at the northern tip of Khortitsa island and a huge statue not too far away in Zaporozhye overlooking the island. There are two monuments in Kiev, one on Peyzazhnaya Alleya, one near the Tripolye Culture Park and another one in Starye Petrovtsy not far from his mum’s estate in Vyshgorod. Moving away from the description given by Leo the Deacon, there was a bearded, but un-moustachioed Svyatoslav in Mariupol, set up by the extreme right Azov movement. As is the case with Azov, the statue isn’t there any more. In Kholki, near Belgorod, we have another controversial statue. Aspects of the design were changed after complaints of possible anti-semitism – the fallen Khazar’s shield originally had a Star of David on it, representing the Judaism of the Khazar rulers. This was altered to a more neutral six-sided geometric design. We have a statue in Serpukhov, and one in our old favourite, the Alley of the Rulers of Russia in Moscow. Finally Svyatoslav appears on the Millennium of Russia monument in Novgorod.

There were four ships of the Imperial Russian navy named in honour of Svyatoslav, a Ukrainian silver coin was released to remember him and although he’s only a little baby, he does appear on the 2012 Russian stamp.

I decided that Saints would get extra points, but as the first pagan ruler to die in battle and (assuming he was still to a certain extent a Norse pagan) therefore the first to get to Valhalla, he should get some extra points as well. He doesn’t quite match up to his mum on this, but he still gets a well deserved 18 points out of 20.

Reflected Glory: We have already considered Sveneld under Olga’s rule, but another figure from Igor’s time might have had a moment of dubious glory under Svyatoslav: Igor, the nephew of Igor Rurikovich. He was mentioned immediately after Svyatoslav in the list of notables who sent a personal envoy to the negotiations with the Romans in 943 and it is believed he might, as commander of the avant-guard of Svyatoslav’s army, have been the tall, well-built “giant” Leo the Deacon reports as being sliced in two by Bardas Sclerus at Arcadiopolis.

Svyatoslav’s Rating: 65 out of 100

In our next episode we find out how Yaropolk does after his unexpected accession as Grand Prince.

- The official dating raises a number of doubts: The Hypatian Codex gives Svyatoslav’s date of birth as 942, but no other versions of the PVL mention a date. There are a number of historians who think he may have been older. A birth date in 942 would make him three or four when he rode to battle against the Drevlyane in 946, about fifteen in 957 when his mother left him in charge at Kiev for her visit to the Emperor, and nineteen when he dismissed the western missionaries his mother had invited. From earlier entries in the PVL and her later hagiography, Olga would most likely not have been a young lady in 942 either – probably around fifty. It would not impossible that she should bear a child, but getting quite unlikely. A number of historians have proposed Svyatoslav might have been born earlier on the basis of Olga’s age and Svyatoslav’s riding ability. Some place his birth date in 927, but that in that case, it seems very odd that an eighteen year old should need his mother to take power on his behalf in 945.

I find Leontiy Voytich’s suggestion of 938 more convincing. It would make Olga forty-five or so at his birth, still old, but more likely to be fertile and it would make Svyatoslav eight in 946 – not old enough to rule, but old enough to ride and attempt to throw a spear. He would have been twenty when his mother left for Constantinople – more than old enough to take over. The invitation of the missionaries, taken as Olga’s last known action as regent (and the reason for the c. 960 date for the end of her rule and not 957) might even have been a more or less private move by her – the PVL shows Svyatoslav took no interest towards Christianity – if his mother wanted to discuss her new religion with a German bishop, that might have been considered purely her business. An slightly older Svyatoslav would also explain how he was able to father three children who were of an age to indulge in a civil war not long after he died. He could have been a really early starter but those extra five years would make things seem a bit more likely. ↩︎ - The Khazars have attracted some interest because of the decision of the leadership to convert to Judaism in the 8th century AD. The Khazar Khaganate was an empire based in the steppes between the Black Sea and Caspian Sea, which arose in the wake of the collapse of the Western Turkic Khaganate in around 650AD. The original Khazars were nomadic Turks, who followed their folk religion known as Tengrism. The Khazars found themselves occupying part of the trade route between Scandinavia and the Caliphate as well as the northern Silk Road routes across Central Asia to the Roman Empire and Europe.

The Khazar state had a system of dual rule. The Khagan was a spiritual leader who was not expected to actually rule. According to Ibn Fadlan he would be partially asphyxiated during the coronation and in a state of oxygen depletion would prophesy as to the length of his reign. At the date specified, he would be killed and replaced. If he survived for forty years, he would be sacrificed regardless of how long he had prophesied.

The active rule was carried out by the Khagan-Bek, who commanded an army of around 10,000 men and who could call on the retinues of Khazar nobles and of vassal peoples if more men were required. The Khazars expanded their rule over large areas of the steppe to the north of the Black Sea, into central Asia up to the Aral Sea, up the valleys of the Volga and Don and south beyond the Caucasus. This meant that, aside from the Khazar nobility and warrior class, they had a large multi-ethnic and multi-religious population united only by paying tribute to the Khagan.

As they neighboured the Christian Roman Empire and the Muslim Abbasid Caliphate, the Khazars had fallen under some diplomatic pressure to convert to one or other of these religions. However, the rulers at least ended up converting to Judaism at some point in the 8th century. It is suggested this choice might have been made precisely to retain a degree of neutrality in dealings with their southern neighbours, while allowing them to take advantage of the organisational strengths of a literate monotheistic religion. The Abbasid Caliphate had a thriving Jewish community in Mesopotamia active in the trade to the north, while the Roman Empire had been periodically persecuting Jews, driving people to look for a safe home elsewhere.

However, it has been thought that the choice of Judaism might have been one of the causes of the fragility of the Khaganate when faced with the Russian state. Many of the nations on the periphery of Khazar rule had converted or were converting to Islam or Christianity by the 10th century and these associations were used by both Roman and Abbasid diplomats to try and draw factions and subject nations over to their side. The case of the Muslim Khazar Royal Guard attacking the Russian raiders of the southern Caspian in the 940s although the Khagan-Bek had given them safe passage shows an example of religious affiliation trumping political alliegiance. Another possible example of this is a rebellion of three tribes of Khazars known as the Kabars in the early 9th century after the conversion of the rulers. The Kabar rebellion was crushed and the survivors driven into exile to join the Magyars, but given the relatively small Khazar ruling class, this would have weakened the state, maybe explaining its inability to prevent first Askold and Dir, then Oleg from removing a number of Slavic tribes from Khazar control in the late 9th and early 10th centuries.

Svyatoslav’s campaign seems to have sent the Khazar Khaganate into rapid and permanent decline. Although mention is made of a residual Khazar presence in the area for some time, they are now one tribe among many and never again play a dominating role in the territory they ruled for three centuries. By the middle of the 11th century, their old stamping grounds had been conquered by the Polovtsy – another group of Turkic speaking nomads from Central Asia.

Much of their current fame is due to a theory that the Ashkenazi Jews of Eastern Europe are not really Jews at all, but the descendants of Khazars. This has been pretty much refuted by DNA analysis, although “Khazar” is still used as an unsympathetic reference to Jews which is less likely to be identified as anti-Semitic. ↩︎

Leave a comment